Immunizations

Highlights

Seasonal Flu Vaccine

- In its 2012 guidelines, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that everyone (healthy as well as at higher risk) 6 months of age or older receive annual flu vaccination unless there are medical reasons to avoid vaccination.

- Two new vaccines were released in the spring of 2011, Fluzone Intradermal and Fluzone High Dose. The intradermal vaccine contains a smaller amount of vaccine compared to standard flu shots and is injected into the skin instead of the muscle. The high dose vaccine contains four times the amount of vaccine compared to the standard flu shot. It is available for adults ages 65 and older.

Meningitis

- A quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine, MCV4-D (Menactra), is now available for children between 9 months and 23 months of age. The vaccine may be recommended for children who have been exposed to the infection and for those with deficiencies of the complement system, which is part of the immune system.

- Others may receive MCV4-CRM (Menveo) at 2 years of age and older.

Human Papillomavirus Vaccine

- The CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the American Academy of Pediatrics now recommend that all boys ages 11 - 12 have routine vaccination with Gardasil, with catch- up vaccinations for boys and men ages 13 - 21. ACIP also now recommends that men ages 22 - 26 with compromised immune systems, HIV, or men who have sex with men (MSM) be vaccinated against HPV.

Tetunus, Diptheria, Acellular Pertussis (Tdap, Td)

- Full vaccination (3 doses) of Tdap is now recommended for all previously unimmunized adults who are in close contact with infants up to 12 months of age (such as parents, grandparents and child care givers).

- Adults who were previously vaccinated, and have contact with infants up to 12 months of age, should receive a one-time dose of Tdap.

- While Tdap was once reserved for mothers after delivery, Tdap is now recommended for all pregnant women after 20 weeks gestation.

Shingles

- The FDA recently approved administration of the Zoster vaccine to people ages 50 and older for the prevention of shingles. ACIP however continues to recommend the vaccine begin at age 60.

Schedule for Adults Based on Medical and Other Indications

- MSM, or men who have sex with men, has been added as a new category in the vaccination schedule for specific higher risk groups based on medical and other indications.

- Diabetics are now included in the high risk group with kidney diseases. It is now recommended that diabetic patients under 60 years of age be vaccinated against Hepatitis B. Older diabetic patients who use blood glucose monitoring devices or have other risk factors may also be considered for Hepatitis B vaccination.

Introduction

Immunizations against childhood diseases save millions of lives. American vaccination rates are now at an all-time high. Illness and death from diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella (German measles), and Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) type b are at or near record lows. In adults, immunizations against influenza (the flu), pneumococcal pneumonia, hepatitis, and other ailments have likewise saved many lives and prevented many cases of serious illness. A new vaccine has been shown to be highly effective against the virus that causes cervical cancer as well as many cases of genital warts and oral and anal cancer.

More than 70 bacteria, viruses, parasites, and other infectious microbes cause major human disease. Fortunately, vaccines are either available or being developed against a portion of them. With the advent of new or newly feared biological threats, emerging infections, and bacterial resistance to common antibiotics, immunizations are assuming an increasingly important role in maintaining the health of billions of people worldwide.

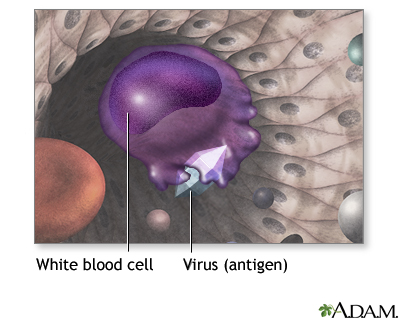

Immunization exposes you to a very small, very safe amount of the most important infections. This exposure helps your immune system recognize and attack the infection and prevent the disease it may cause. If you are exposed to the full-blown disease later in life, you will either not become infected or have a much milder infection.

Vaccine Forms

Most vaccines are given by an injection, but some can be taken orally (by mouth) or by a nasal spray. They usually contain one of four components that cause an immune response:

- A live but weakened virus. Live-virus vaccines provide longer immunity than inactivated ones, but they can cause serious infection in people with weakened immune systems, and have also been associated with severe medical disorders in rare instances.

- Inactivated bacteria, viruses, or toxoids. Inactivated vaccines are safe even in people with impaired immune systems.

- A toxoid is an altered form of a harmful substance (toxin) released by certain bacteria. The toxoid in vaccines is changed so it does not harm the person but still produces an immune response.

- Bacterial or viral components are not the whole organism. They are only parts of the microbe that trigger a strong immune response.

The harmless infectious component in the vaccine teaches the immune system to recognize the full-strength, live, and harmful substance or organism. The immune system then knows to attack it when real exposure occurs. The antibodies produced in response to the vaccine remain in the body, preventing future illness from such an exposure. This is called immunity.

Combination Vaccines. The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family Physicians recommend that health care providers use, whenever possible, combination vaccines instead of individual components. Combination vaccines for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) -- and for measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) -- have been available for many years.

New combinations that cover up to 5 vaccinations are being developed and are proving to be safe and well tolerated in infants as young as 2 months. For example, one that combines DTaP, hepatitis B, and the polio vaccine (Pediarix) is available. It is as effective as the individual vaccines when given to children ages 6 weeks to 6 years.

There is some concern that increasing use of combinations may reduce the potency of some of the vaccines. Some parents are also worried about increased side effects. Studies to date, however, are reporting that combinations are effective and safe.

Passive Immunity. Another form of protection against disease is called passive immunity. This approach uses immune globulin, which are blood products containing antibodies. Immune globulin is generally used for people who cannot be vaccinated, when immediate protection is required, or to prevent severe complications of the disease. In some circumstances, passive immunity can interfere with active vaccinations, particularly live-virus vaccines. Therefore, if possible, these two immunization types should not be administered within weeks or even months of each other.

General Information on Side Effects. Vaccines can have side effects, which are nearly always mild, such as swelling at the injection site or fever. There have been a number of reports in the popular press about alarming side effects in many vaccines. Anti-vaccine groups vocally oppose immunizations in children. Although it is true that no vaccine is 100% safe, childhood infections have not been wiped out. Without immunization, parents risk exposing their children to diseases that in the past have killed millions of young children.

General Guidelines

Routine Childhood Vaccines. Experts recommend that all children be routinely vaccinated against the following diseases:

- Measles

- Mumps

- Rubella (German measles)

- Diphtheria

- Tetanus

- Pertussis (whooping cough)

- Poliomyelitis (polio)

- Varicella (chickenpox)

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis A

- H. influenzae type b (a cause of meningitis)

- Influenza (children aged 6 months to 18 years)

- Pneumococcal disease

- Meningococcal disease (recommended for all children ages 11 and up; recommended for high-risk children 2 - 10 years of age).

- Rotavirus (children aged 6 - 32 weeks)

Many vaccinations are first given during infancy. Even premature infants can, in most cases, be given vaccinations on a normal schedule. Note: These facts pertain to children in the United States. Children from other countries have not been well studied. Parents who adopt internationally may want to have their children's immunity assessed by a physician. Some evidence suggests that their medical records may not correctly reflect immunization status and that many adopted children, such as those from China, have not had many important vaccinations.

Common Adolescent and Adult Vaccines. Vaccinations against the following disorders are also recommended routinely for certain adults. More information on these vaccines is discussed in the Specific Vaccinations section:

- Influenza (flu) (highly encouraged for all adults)

- Pneumococcal pneumonia.

- Hepatitis A and B

- Meningococcal vaccine.

- Tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis.

- Measles, mumps, rubella.

- Herpes zoster (shingles) vaccine

- Human papillomavirus (HPV)

- Varicella (chickenpox)

Vaccination Recommendations During Pregnancy

Inactivated-virus and toxoid vaccines are usually safe in pregnant women, although any vaccination should be delayed, if possible, until the second or third trimester. Because of a possible risk to the fetus, live-virus vaccines should not be given to pregnant women or those likely to become pregnant within 28 days unless such women need immediate protection against life-threatening diseases, such as yellow fever, that are only prevented using live-virus vaccines. The live-virus MMR combination, which vaccinates against measles, mumps, and rubella, is not given to pregnant women because of the theoretical risk of the live-rubella vaccine to the fetus.

Vaccination Recommendations for People with Compromised Immune Systems

In general, vaccines are not completely effective for patients whose immune systems are compromised by disease or medications. Often, such patients are given immune globulin if they are exposed to infection. It may take 3 months to 1 year before a person who has stopped taking immunosuppressant drugs to regain the full ability to be successfully immunized against disease.

Live-virus vaccines are not usually given to people whose immune system has been compromised by illness or by the use of medications.

People who should not get live-virus vaccinations include:

- Persons who have immune deficiency diseases (such as HIV or AIDS).

- Patients with active leukemia or lymphoma.

- Patients who are receiving treatments that suppress the immune system, such as corticosteroids, alkylating drugs, antimetabolites, or radiation. (There are important exceptions, however, which are noted in the discussion of individual vaccinations below.) Short-term corticosteroids (given for less than 2 weeks) should not affect any live-virus vaccination. Patients who need vaccinations and who take long-term or high-dose topical steroids should check with their physicians.

| Childhood Immunization Schedule** | |||||

Age | Chickenpox (Varicella Zoster) | Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis (DTaP)* | Haemophilus influenzae type (Hib)** | Hepatitis A | Rotavirus |

Birth | |||||

2 months | DTaP* | Hib | Rotavirus | ||

4 months | DTaP* | Hib | Rotavirus | ||

6 months | DTaP* | Hib (Depending on brand. For example, no third dose is required for PedvaxHIB or ComVax.) | Rotavirus (not needed if Rotarix was administered at 2 and 4 months) | ||

12 - 15 months | Varicella | DTaP* (Typically between 15 and 18 months. May be given as early as 12 months in high-risk children as long as 6 months have passed since the third dose.) | Hib (Sometime between 12 and 15 months. (TriHiBit, a DTaP/Hib combination vaccine, can be used for this dose) | HepA (In 2 does, between 12 and 23 months) | |

2 years old | In children who have not been fully vaccinated. | ||||

4 - 6 years | Varicella | DTaP | |||

| 7 - 10 years | Tdap (if indicated) | ||||

11 - 12 years | Varies. (If previously missed, two doses should be given at least four weeks apart.) | Tdap (up to 18 years of age) | In adolescents through age 18 in selected areas. | ||

Age | Hepatitis B (Hep-B)* | Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) | Pneumococcal Vaccine (PCV) | Polio (Inactive virus) (IPV)* | Human Papillomavirus (HPV) | Meningitis *** | |

Birth | Hep-B before discharge from hospital. (Within 12 hours and with Hep B immunoglobulins when mothers are infected.) * | ||||||

2 months | Hep-B some time between 1 and 2 months depending on risk. * | PCV | IPV* | ||||

4 months | PCV | IPV* | |||||

6 months | Hep-B some time between 6 and 18 months. * | PCV | IPV* (Advised at some point between 6 and 18 months.) * | ||||

12 - 15 months | Varies. | MMR (Some time between 12 and 15 months.) |

(Minimum age is 9 months for MCV4-D) | ||||

2 years old | PCV -- 1 dose for children not previously vaccinated. PPSV for certain high risk groups | MCV4 (for high risk patients- revaccination after 3 years) | |||||

4 - 6 years | MMR | PCV -- 1 dose in high-risk children up to age 59 months. PPSV for certain high risk groups | IPV* | MCV4 (for high risk patients - revaccination after 3 years) | |||

11 - 12 years | Hep-B (If vaccinations were previously missed). Two or 3 doses a few months apart. | MMR (If vaccinations were previously missed). | PPSV for certain high risk groups | HPV -- 3 doses (Females) Also recommended routinel for males (Booster at 16 years) | Meningitis -- MCV4 *** | ||

* A one-shot combination vaccine (Pediarix) has been approved that covers polio, hepatitis B, diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DTaP) and should simplify the immunization process. It would be given as a single injection at 2, 4, and 6 months with booster shots given at 12 - 15 months and 4 - 6 years. **All children aged 6 months - 18 years should receive an annual flu shot. Children younger than 9 years of age, who are receiving this vaccine for the first time (or who were vaccinated for the first time during the previous season with only 1 dose) should receive 2 doses of the flu vaccine at least 4 weeks apart. *** Two types of meningococcal vaccine are available. Children and adults under age 55 should receive the MCV4 vaccine. The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations now call for routine vaccination of all adolescents (aged 11 - 18) at the earliest opportunity, ideally at age 11-12. The ACIP also recommends vaccination and booster doses for those previously defined as being at increased risk, including people exposed to single cases or outbreaks; freshmen college students living in dorms; military recruits; travelers to developing countries where outbreaks have occurred; and patients with problems in the spleen. | |||||||

Side Effects and Anti-Immunization Groups

Many parents are worried that some vaccines are not safe and may harm their baby or young child. They may ask their doctor or nurse to wait, or even refuse to have the vaccine. However, it is important to think about the risks of not vaccinating, as well.

Some people believe that the small amount of mercury (called thimerosal) that is a common preservative in multidose vaccines causes autism or ADHD. However, studies have NOT shown this risk to be true.

- Thimerosal is a preservative that has been used in many vaccines since the 1930s. (Preservatives are necessary to prevent vaccine contamination with live organism in vials that are used for vaccinating multiple people.) The amount of mercury introduces into vaccines has been very small (approximately 25 micrograms of mercury per 0.5 mL dose, according to the Food and Drug Administration).

- All vaccines recommended for children aged 6 or younger contain either no thimerosal or only trace amounts of it, with the exception of the inactivated influenza vaccine. (A limited supply of this vaccine, containing only trace amounts of thimerosal, is available for use in infants, children, and pregnant women.) A trace amount means that a given dose of vaccine contains less than 1 part per million.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) all agree that vaccines or any component of vaccines do not cause autism. They conclude that benefits of vaccinations outweigh the risk

Some parents are also worried that they or their child can get the infection from some vaccines, such as the MMR, the varicella, or the nasal spray flu vaccines. However, unless you have a weakened immune systems, this is very, very unlikely.

Like many medications, there is always a chance an immunization can cause adverse events.

Of great concern are anti-immunization organizations and web sites, which were formed mostly because of unsubstantiated reports linking small numbers of serious problems to some vaccines. The following watchdog systems are now in effect to monitor side effects from vaccination:

- VAERS (Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System) is a government service that registers all adverse events reported after vaccination, including those not related to the vaccine. It is useful for surveillance but has limitations. For example, the service may record the same case more than once. In addition, more serious events that occur soon after a vaccination are more likely to be reported than later and milder events, and such events are not necessarily linked to the vaccine.

- VSD (Vaccine Safety Datalink) is a linked database that analyzes the records of more than 5 million patients each year. It is more accurate than VAERS, although the information it contains is not as timely.

- The CDC has established the national network of Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Centers. It provides services to physicians to help them evaluate and manage patients who may have had a side effect.

Studies using these systems are ongoing and none to date have confirmed reports of any significant association between most vaccines and severe side effects that would outweigh the benefits of these important and lifesaving agents.

No vaccine is 100% safe. Allergic and serious reactions are possible. In 2 cases, the early oral live polio vaccine and the first rotavirus vaccine, problems did occur, and some were serious. It is important to note, however, that even in these cases, the vaccines were withdrawn and the severe events were still far fewer than the number of lives saved. Both of these vaccines have been changed and are now safe.

However, deciding not to immunize a child also involves risk. The potential benefits from receiving vaccines far outweigh the potential risks.

- After immunizations were introduced on a wide scale, infections such as tetanus, diphtheria, mumps, measles, pertussis (whooping cough), and polio became rare. All of these illnesses used to lead to lifetime disabilities or even death.

- Newer immunization have also decreased certain types of meningitis, pneumonia, and ear infections in children.

- Pregnant women may contract infections that can be very dangerous to their fetus. Vaccines reduce this risk.

Tips for Helping Small Children Before, During, and After Vaccinations

Infants often accept the first injection easily, since they are not expecting it. It gets more difficult, however, with each additional injection. Simply providing love and warmth can help children of all ages tolerate immunizations.

Additional tips:

- Do not lie and tell an older child that an injection will be painless. Some health care providers suggest telling your child that it stings a little, and to count to 5 while the vaccine is being administered.

- Ask the doctor if it is OK to give the child a dose of acetaminophen (Tylenol) after a vaccination if pain or fever causes distress. Ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) or other non-aspirin pain relievers may be acceptable alternatives. (Children should NEVER take aspirin.)

- A cooling spray may work by numbing the skin a little.

- Longer needles, rather than shorter ones, may help reduce pain.

- Have your child take a deep breath right before the injection and blow out very hard while it is being given.

- Give a sweet fluid before the shot and a little reward, such as a lollipop, immediately after the shot. Sugar actually has mild pain relieving properties for infants.

Symptoms of Severe Reactions to Vaccinations

Although severe reactions are extremely rare, parents should know how to respond.

Call the doctor immediately if a child has any of the following symptoms.

- Extremely High Fever. A rectal temperature of 105 °F or higher. (Temperatures taken under the arm or by mouth often register lower than actual temperatures.)

- Inconsolable Crying. The child has been crying for over 3 hours without stopping or has a cry that isn't normal, such as a high-pitched sound.

- Convulsions. The child's body starts shaking, twitching, or jerking. This is usually in response to a high fever. Place the child face down with the head to one side, protecting the head from hitting anything hard. Be sure the child can breathe freely. A simple febrile seizure stops by itself within a few seconds to 10 minutes.

Seek immediate medical attention if a child has any of the following symptoms

- Shock. The child collapses, turns pale, and becomes unresponsive.

- Severe Allergic (Anaphylactic) Reaction. Swelling in the mouth and throat, wheezing and breathing difficulties, dizziness. The child collapses or is pale and limp.

Call the doctor if the following symptoms persist for more than 24 hours:

- The injection site is still red and tender.

- Fever does not go down.

- The child is still fussy.

Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis

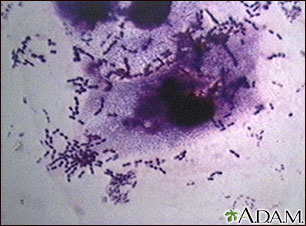

Diphtheria. Diphtheria is caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, which can occur as either a toxic or nontoxic strain. When only the skin is involved, it is known as cutaneous diphtheria, and is likely to be a nontoxic strain. If the toxic strain affects the mucus linings in the body, such as the throat, diphtheria becomes life threatening. Between 1900 and 1925, diphtheria infected 200,000 people every year and killed 5 - 10% of them, mostly the very young and very old. Because of immunizations, only 6 cases were reported in the United States between 2000 and 2003. No cases have been reported and confirmed since 2003.

Tetanus. Tetanus is a disease that causes severe muscular contractions and convulsions. It is caused by a powerful toxin secreted by the bacterium Clostridium tetani. The bacterium is anaerobic, which means it lives without oxygen. People become infected by this dangerous bacterium through skin wounds. It is fatal in 15 - 40% of cases. Only 233 cases were reported in the U.S. between 2000 and 2008, inclusive, mostly in adults.

Pertussis. Pertussis (whooping cough) was a very common childhood illness throughout the first half of the 1900s. The disease is very easily spread from one person to another, and it is most severe in babies. Because of immunizations, cases of whooping cough in the U.S reached an all-time low of 1,010 in 1976. The incidence has risen recently, with 25,827 cases reported in 2004, but dropped to 10,454 in 2007, the last year reported by the World Health Organization. The CDC reports that 16, 858 cases occurred in 2009.

The benefit of the vaccine wears off by adolescence. Therefore, more cases are seen in adults. Such cases may be greatly underreported. The younger a whooping cough patient is, the higher the risk for severe complications, including pneumonia, seizures, and even death. Children younger than 6 months are at particular risk because even with vaccination, their protection is incomplete due to an immature immune system.

Vaccinations for Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis

The Initial Vaccination. Vaccination against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis has been routinely given to children since the 1940s. The standard vaccine now is DTaP. DTaP uses a form of the pertussis component known as acellular pertussis, which consists of a single weakened pertussis toxoid. DTaP is just as effective but has fewer side effects than DTP, the previous vaccine.

The Booster.

- Protection against diphtheria and tetanus lasts about 10 years. At that point a booster may be given against tetanus and diphtheria (Td). The Td vaccine contains the standard dose against tetanus and a less potent one against diphtheria. It does not contain the pertussis component.

- The infant pertussis vaccine can start to wear off after about 5 years, and some previously immunized teens and adults can get a mild form of the disease. There are now two pertussis-containing boosters approved for teens and adults.

DTaP Schedule in Childhood. All children younger than 7 years old should receive the DTaP vaccine. In general, the vaccinations are given as follows:

- Infants receive a series of three vaccinations at 2, 4, and 6 months of age. The only reason to delay a vaccination is in infants with suspected neurologic problems until their neurologic situation is clarified. Children with neurological problems that have been corrected can be vaccinated. (This vaccine should be given no later than their first birthday).

- A fourth dose is given between 15 and 18 months. (Infants at higher risk, such as those exposed to an outbreak of pertussis, may be given this vaccine earlier.)

- A fifth dose is given at 4 - 6 years. This fifth dose now usually includes a vaccine against H. influenzae as well.

- Children between the ages of 11 and 15 years old should receive a DTaP booster shot.

If a child has a moderate or severe current or recent fever-related illness, vaccinations should be postponed until after recovery. Colds or other mild respiratory infections are no cause for delay. Parents should not be unduly concerned if the interval between doses is longer than that recommended. The immunity from any previous vaccinations persists, and the doctor does not have to start a new series from scratch.

Recommendations for Adults. Many people are currently not getting routine boosters.

All adults who have been fully vaccinated either as a child or an adult should have a Td booster at least every 10 years. If they had not received a DTaP vaccination after age 19, they will need it for the next booster, but not afterwards. Adults with regular contact with infants under 12 months of age should receive a one-time Tdap booster.

Adults who have not previously been immunized to diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis at any age:

- Should receive a series of three doses. One may be the tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccine.

- If she is pregnant, a woman should receive the Tdap vaccine after 20 weeks gestation.

Any patient who requires medical care for any wound may be a candidate for a tetanus vaccine. Wounds that put patients at highest risk for tetanus are puncture wounds or wounds contaminated with dirt or feces. Some considerations for tetanus vaccinations in wounded people are as follows:

- A booster is needed if the last dose was given 5 or more years before the injury.

- Children under 7 are usually given DTaP if they are not fully vaccinated.

- Patients who have not completed their primary series of tetanus immunizations and people who had experienced an allergic response to a previous tetanus booster may be given tetanus immune globulin (TIG).

Side Effects of Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis (DTP) Vaccine

Allergic Reactions. In rare cases, people may be allergic to the older diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine, DTP. Parents should tell their doctor if their children have any allergies. The newer vaccine, DTaP, may pose a slightly higher risk for an allergic reaction than the older vaccine, DTP. Children who have severe responses should not be given further vaccinations. A rash that occurs after a dose of DTP is of little consequence. In fact, it does not usually indicate an allergic response but only a temporary immune reaction and does not usually recur with subsequent shots. It should be noted that no deaths have been reported from allergic reactions, even severe (anaphylactic) ones, to the DTP vaccine.

Pain and Swelling at the Injection Site. Children may feel pain at the injection site. In some cases, a small lump may remain at the site for several weeks. Placing a clean, cool washcloth over any swollen, hot, or red area can help. Children should not be covered or wrapped tightly in clothes or blankets.

The risk for swelling, including of the whole arm or leg, increases with subsequent injections, particularly the fourth and fifth doses. If possible, parents should request that their children receive the same vaccine brand each time to help reduce the risk of side effects.

Fever and Other Symptoms. A child may develop a mild fever, irritability, drowsiness, and loss of appetite after a shot.

The following remedies may be helpful:

- Acetaminophen (for example, Children's Tylenol) and a sponge bath in lukewarm -- NOT cold -- water may help relieve fever and pain.

- The doctor may suggest that children who have had previous high fevers or other reactions to the injection be given acetaminophen at the time of the vaccination and every 4 hours afterward for 24 hours. (The doctor will determine the dosage according to the weight of the child.)

- NEVER give aspirin to children.

Fevers that should cause concern include the following:

- Any very high fever (over 105 °F) that causes seizures in children should be reported immediately to the doctor. The newer DTaP vaccine has significantly reduced the risk for this side effect when compared to older vaccinations. Although frightening, such fever-related seizures are uncommon and rarely have long-term effects. A recurrence after a subsequent vaccination is very unlikely.

- A new fever that develops 24 hours after the vaccination, or a fever that persists for longer than 24 hours are most likely due to other causes and not the vaccination. This is true also for seizures that develop after 24 hours.

Hypotonic-Hyporesponsive Episode (HHE). HHE is an uncommon response to the pertussis component and occurs within 48 hours of the injection in children under 2. The child usually starts out feverish and irritable and then becomes pale, limp, and unresponsive. Breathing is shallow, and the child's skin may turn bluish. The reaction lasts an average of 6 hours and, although it is frightening, virtually all children return to normal. This side effect is less common since the introduction of the DTaP vaccine, but it can still occur.

Neurologic Effects in Pertussis Component. Of concern have been a few reports of permanent neurologic abnormalities that have occurred after children have been vaccinated. Such reports include attention deficit disorder, learning disorders, autism, brain damage (encephalopathy), and even death.

It is well established that the diphtheria and tetanus components cause no adverse neurologic effects, so some people suspect the pertussis component. However, many major studies found no causal relationship between neurologic problems and the pertussis vaccination. Studies on the newer DTaP have reported no safety concerns to date.

Studies suggest that in cases where neurological problems have been strongly linked to the vaccination, high fevers -- not immunization -- are responsible. Children with known neurological abnormalities may also be at risk for an outbreak of symptoms 2 or 3 days after the vaccination. Such a temporary worsening of their disease rarely poses a danger to the child. Children who have new neurologic events following their vaccination may already have a preexisting but unknown condition, such as epilepsy, which is revealed -- but not caused -- by the vaccine. To date, there is no proof that the pertussis vaccine causes these neurologic events, which, in any case, are so infrequent as to be nearly impossible to evaluate in relationship to any event that preceded them.

Important Note: Unwarranted fears of side effects from vaccinations can be dangerous. In England such fears have caused a significant decline in immunization rates since the 1970s. Outbreaks of whooping cough have occurred as a result, causing a number of deaths and brain damage in many children. Small babies are particularly endangered if they become infected from older unvaccinated children (who usually have a mild disease).

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

Measles. Measles, one of the most contagious of all human infections, used to be a very common childhood disease. Most cases resolve without serious complications. In severe cases, however, measles can cause pneumonia, and in about 1 out of 1,000 cases it can lead to encephalitis (inflammation in the brain) or death. The risk for these severe complications is highest in the very young and very old. In pregnant women, measles increases the rates for miscarriage, low birth weight, and birth defects.

Aggressive vaccination programs have reduced the incidence of measles in the U.S., to a low of 118 cases in 2011, most imported from other countries.

Mumps. Mumps is at record lows in the US, with 800 cases reported in 2007. In about 15% of cases, mumps affects the lining of the brain and spinal cord, although this is usually not ultimately harmful. Swelling of the testicles occurs in 20 - 30% of males who have reached puberty, although sterility is rare. Deafness in one ear occurs in one patient out of 20,000 with mumps.

Rubella (German Measles). When rubella, commonly known as German measles, infects children or adults, it causes a mild illness that includes a rash, enlarged lymph nodes, and sometimes a fever. If a pregnant woman is infected during her first trimester, however, her baby has a 80% chance for developing birth defects, including heart abnormalities, cataracts, mental retardation, and deafness.

Before the vaccine became available, about 56,000 cases of rubella occurred annually in the U.S. Vaccination programs have dramatically reduced the number of cases to a low of 12 in 2007, but 6 - 11% of adults are still susceptible, particularly unvaccinated Hispanic Americans who were born outside of the U.S.

Vaccines for Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

Safe and effective live-virus vaccines for measles, mumps, and rubella have been developed over recent decades. They are usually combined in children as the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and most recently include the varicella (chickenpox) vaccine as well (MMRV). Individual live-virus vaccines or the combined MMR may be given to adults, depending on their risk factors.

Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) or Measles-Mumps-Rubella-Varicella (MMRV) Vaccine in Early Childhood. In September 2005, the combination vaccine MMRV including measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (chicken pox) was licensed in the U.S. The vaccine has been under study due to reports of increased fevers post vaccination. The CDC concluded in June 2009 that the use of the combination MMRV or separate MMR and varicella vaccines are both safe and effective and either approach may be used. The combined MMR or MMRV vaccine should be given in two doses:

- Between ages 12 and 15 months for the first dose

- Between ages 4 and 6 years for the second dose. (Children who receive only one dose at 15 months or older have five times the risk of measles compared to those who had two doses.)

Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) Vaccine in Adolescents and Adults. The general recommendations for adult MMR vaccinations are as follows:

- Most people born before 1957 have experienced these once-common childhood diseases and do not require vaccination.

- All unvaccinated people born after 1956 who did not already have measles and mumps should be given two doses, administered at least 1 month apart, (adolescents) or 1 dose (adults) of the live MMR vaccine.

- Many people received an inactivated measles-virus vaccine in the early 1960s or an inactivated mumps-virus vaccine between 1950 and 1978; such people need revaccination with two doses of the live MMR vaccine. (This will cause no harm even if someone had a previous live-virus-mumps vaccination.)

- The American Academy of Pediatrics now recommends the live-virus MMR vaccine for HIV-infected children, teenagers, and young adults, except for those who are severely immunocompromised. The vaccine appears to be safe in HIV-infected children, and it should be stressed that measles is very dangerous in this population.

Rubella Vaccinations During Pregnancy. It is particularly important for any unvaccinated nonpregnant woman who wants children to be vaccinated against rubella. It is recommended that women wait at least 28 days after vaccination to start trying to conceive. Except under very special circumstances, no live-virus vaccine, especially MMR, is given to an already pregnant woman, since there is a theoretical risk for birth defects from these vaccines. Fortunately, the risk is low. In fact, studies have reported no increase in birth defects in women who were inadvertently vaccinated for rubella early in their pregnancy.

The following people should not receive the MMR vaccine:

- Pregnant women and women who might become pregnant within one month of vaccination

- Certain HIV infected individuals

- People whose immune systems are compromised by disease or drugs (such as after organ transplantation)

Side Effects of Live Measles Mumps-Rubella (MMR) Vaccines

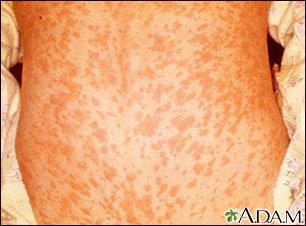

Common side effects from the MMR vaccination include fever, rash, and joint pain. Most of these side effects are less frequent after the second dose; however, teens and adults who receive this vaccine are more likely to suffer from joint pain and stiffness.

Fever. About 5 - 15% of people who are vaccinated with any live measles virus vaccine develop a fever of 103 °F or greater, usually 5 - 15 days after the vaccination. It usually lasts 1 or 2 days but can persist up to 5 days. In very young children, seizures can occur from high fever 8 - 14 days after vaccination, but they are rare and almost never have any long-term effects.

Swollen Glands. The live-mumps vaccine can cause mild swelling in the glands that are situated near the ears.

Joint Pain. Up to 25% of women have joint pain 1 - 3 weeks after a vaccination with a live-rubella virus; it lasts for 1 day to 3 weeks. Such pain does not usually interrupt daily activities. Rarely, it recurs or becomes persistent.

Allergic Reaction. People who have known anaphylactic allergies (very severe reactions) to eggs or neomycin are at high risk for a severe allergic response to the MMR vaccine. People with allergies that do not cause anaphylactic shock to these substances are not at higher risk for a serious allergic reaction to the vaccine. Mild allergic reactions, including rash and itching, may occur in some people. A rash occurs in about 5% of people who are vaccinated with a live-measles vaccine. A live-mumps vaccination has caused rash and itching, but these symptoms are usually mild.

Interaction with Tuberculosis Test. The live-measles vaccine may interfere with a tuberculosis test, so the two should be administered at least 4 - 6 weeks apart. No evidence exists that the vaccine has an adverse effect on tuberculosis itself.

Mild Infection. A mild form of measles that has no symptoms may develop in previously immunized people who are exposed to the virus, although this mild infection may not be significant.

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP). In about 1 in 22,300 doses, MMR can cause a rare bleeding disorder called idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). This can cause a purple, bruise-like discoloration that can spread across the body, nose bleeds, or tiny red spots. It is nearly always mild and temporary. (Of note, the risk for ITP is much higher with the actual infections, particularly rubella.)

Note: Much controversy has arisen over unsubstantiated reports of neurologic side effects attributable to MMR. This is of great concern since such reports have resulted in a decline in immunizations in certain areas, notably affluent areas in England where the vaccination rate has dropped from 92% in 1996 to 84% now. Here, measles outbreaks are now climbing, and doctors fear that unless immunization rates increase rapidly, case numbers will significantly increase. In these and other regions, some parents mistakenly believe that the dangers of immunization outweigh a dangerous childhood illness that only older people remember. It should be strongly noted that measles still cause about 745,000 deaths in unvaccinated children who live in underdeveloped countries, primarily in Africa.

Most publicity has centered on a possible link between the MMR vaccine, which was introduced in 1988, and a variant of autism that includes inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and impaired behavioral development. Such findings have been rigorously reviewed and refuted in a number of well-conducted studies.

Despite considerable publicity, there is no evidence linking MMR vaccination with the development of autism. The CDC's website provides extensive information on this matter. The popular media has incorrectly reported the possible link between autism and MMR as causing a split in the scientific community, but virtually all experts refute any association between the two. In fact, reports of symptoms related to autism increased only after widespread publicity of this supposed side effect.

The potential benefits from receiving the MMR vaccine far outweigh the potential adverse effects. Measles, mumps, and rubella are all very serious illnesses and each may have complications resulting in lifetime disabilities or even death. The incidence of such complications, related to having the actual diseases, is far greater than the potential of developing serious, or even moderate, adverse effects due to the MMR vaccine.

Varicella-Zoster Virus (Chickenpox)

Chickenpox (caused by the varicella-zoster virus) is one of the most contagious childhood diseases. Nearly every unvaccinated child becomes infected with it. The affected child or adult may develop hundreds of itchy, fluid-filled blisters that burst and form crusts.

The infection rarely causes complications in healthy children, but it is not always harmless. Five out of every 1,000 children are hospitalized and, rarely, it can be fatal. Before the vaccination became widespread, chickenpox resulted in about 11,000 hospitalizations and 100 deaths a year.

Chickenpox can be especially severe in adults and very serious in anyone with a compromised immune system. In addition, the varicella virus (which persists in the body after the childhood disease is gone) erupts as a painful and distressing condition called herpes zoster (shingles) in about 20% of adults with a history of chickenpox. Chickenpox itself usually occurs only once, although a few cases of mild second infections, marked by the telltale rash, have been reported in older children years after their first infection.

Vaccines for Chickenpox

A live-virus vaccine (Varivax) produces persistent immunity against chickenpox. Data show that the vaccine can prevent chickenpox or reduce the severity of the illness even if it is used within 3 days, and possibly up to 5 days, after exposure to the infection.

Recommendations for the Vaccine in Children. The vaccine against chickenpox is now recommended in the U.S. for all children between the ages of 12 months and adolescence who have not yet had chickenpox. Children are given 2 doses of the vaccine. The first dose is recommended at age 12 - 15 months. The second dose should be given at 4 - 6 years. However, doses can be as little as 28 days apart (note that the ideal minimum time for children under 13 years is 3 months). To date, more than 75% of children have been vaccinated.

Doctors recommend that the chickenpox vaccine be given at the same time as the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine or that there is a delay of at least 1 month between the two vaccinations. (If the chickenpox vaccination is given within that 30-day period -- but not at the same time -- there is a higher risk for a breakthrough infection later on.) A combined vaccination (MMRV) including measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (chickenpox) is also available.

A chickenpox vaccine is part of the routine immunization schedule. It is about 100% effective against moderate or severe illness, and 85 - 90% effective against mild chickenpox in children. Parents often express concern that the immunity from the vaccine might not last. The chickenpox vaccine, though, is the only routine vaccine that does not require a booster.

Recommendations for the Vaccine in Adults.

Healthy adults without a known history of chickenpox, and who do not show immunity through testing, should receive 2 doses of the vaccine. Special attention should be given to the following groups:

- Older people without a history of chickenpox and who are at high risk of exposure or transmission (such as hospital or day care workers and parents of young children)

- People who live or work in environments in which viral transmission is likely

- Nonpregnant women of childbearing age

- Adolescents and adults living in households with children

- International travelers

As with other live-virus vaccines, the chickenpox vaccine is not recommended for the following people:

- Pregnant women (including the 3 months prior to pregnancy).

- Certain HIV infected individuals.

- People whose immune systems are compromised by disease or drugs (such as after organ transplantation). The vaccine is being studied, however, for its safety in some of these patients, particularly children with cancer or other high-risk conditions. An inactivated varicella vaccine may be safe and effective in patients undergoing bone marrow transplants, when given before and after the operation.

Most patients who cannot be vaccinated but are exposed to chickenpox are given immune globulin antibodies against the varicella virus. This helps prevent complications of the disease if they become infected.

Side Effects of the Chickenpox Vaccine

Discomfort at the Injection Site. About 20% of vaccine recipients have pain, swelling, or redness at the injection site.

Mild Rash and Risk of Transmission. The vaccine may produce a mild rash within about a month of the vaccination, which has been known to transmit chickenpox to others. Individuals who have recently been vaccinated should avoid close contact with anyone who might be susceptible to severe complications from chickenpox, until the risk for a rash has passed.

Severe Side Effects. Between 1995 and 2001, 759 serious adverse effects were reported. Such events included seizures, pneumonia, anaphylactic reaction, encephalitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, neuropathy, herpes zoster, and blood abnormalities. Anecdotal reports have found a higher association of side effects when varicella vaccine is given at the same time as the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination. Because combined vaccinations are being developed, such effects should be closely studied.

Long-Term Protection and Booster Shots

There is intense debate over the long-term protection of the vaccine. However, any negative studies to date on long-term effectiveness simply raise the question of the need for booster or higher doses -- not the elimination of the vaccine altogether.

Long-Term Protection in Vaccinated Children. Most studies suggest that the vaccine is not wholly effective in up to 30% of vaccinated children. However, they also report if chickenpox occurs, more than 95% of the cases are mild. It is also usually less contagious. In such people, the infection appears to be caused by a wild virus, not a reactivation of the vaccine. The longer the interval since vaccination occurs, the higher the risk for a breakthrough infection.

Long-Term Protection in Vaccinated Adults. The protective effects for adults are even less clear.

Vaccine's Effect on Shingles. A primary concern is whether the vaccine protects against shingles later on, particularly in people who have breakthrough infections -- however mild. As more and more children get vaccinated, the actual protection of the vaccine and the implication of the breakthrough infection will become clearer.

[For more information, see In-Depth Report #82: Shingles and chickenpox (Varicella-zoster virus).]

Varicella-Zoster Virus (Shingles)

Shingles is an infection caused by the varicella zoster virus, the same virus responsible for chickenpox. Once a person has chickenpox, the virus lies dormant in the body. It can emerge years later as shingles.

Shingles causes a painful, red, and sometimes blistery rash to form on the body or face. The disease can cause intense pain, called post herpetic neuralgia. Other symptoms include fever, headache, and chills. In rare cases, complications, such as pneumonia, blindness, and brain inflammation (encephalitis), can occur. Shingles is most common in adults over age 50.

Vaccines for Shingles

In May 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration licensed the herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for the prevention of shingles. The vaccine can reportedly cut the incidence of shingles in half for adults over age 60, but its effectiveness declines with increasing age.

Recommendations for the Vaccine in Adults. Most adults age 60 or older should get a single dose of the herpes zoster vaccine, regardless of whether they have previously had shingles. The FDA has approved the Zoster vaccine for adults ages 50 and older, but ACIP currently recommends the single dose vaccination for people 60 and older.

The following people should not receive the herpes zoster vaccine:

- Anyone who has a weakened immune system due to HIV/AIDS or cancer of the lymph, bone, or blood, or due to treatments such as radiation or long-term corticosteroids

- Women who are pregnant, or anyone who is in close contact with a pregnant woman who has not had chickenpox

Side Effects of the Herpes Zoster Vaccine

Redness, pain, and swelling. About a third of the people who get the vaccine have mild redness, soreness, swelling, or itching at the injection site.

Headache. About 1 in 70 people experience headache after receiving the vaccine.

There have been no serious side effects reported with the shingles vaccine.

Long-Term Protection

Research has found that the herpes zoster vaccine reduces the incidence of shingles by about 50%. The benefit is as high as 64% in people ages 60 - 69, but declines to 18% in the group of adults older than 80 years. In people who are vaccinated but still develop shingles, the vaccine reduces the duration of the pain involved with the disease.

Hepatitis A

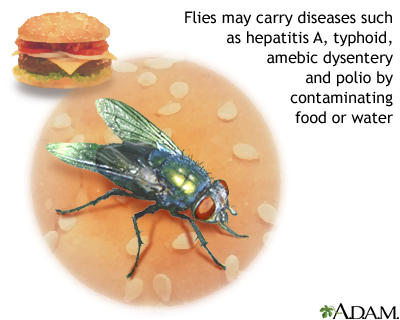

The hepatitis A virus infected an estimated 56,000 people in 2004. Hepatitis A, formerly called infectious hepatitis, is always acute and never becomes chronic. The virus is excreted in feces and transmitted by contaminated food and water. Eating shellfish taken from sewage-contaminated water is a common means of contracting hepatitis A. It can also be acquired by close contact with individuals infected with the virus. It is estimated that 11 - 16% of reported cases occur among children or employees in daycare centers or among their contacts. The hepatitis A virus does not directly kill liver cells, and experts do not yet know how the virus actually injures the liver.

Vaccines for Hepatitis A

All children should get 2 doses of the hepatitis A vaccine starting at 1 year, according to CDC recommendations. The doses should be given at least 6 months apart. Others who should be vaccinated against hepatitis A include travelers to developing countries, people living in communities where outbreaks occur, people with blood-clotting disorders, sexually active homosexual men, and health care workers exposed to the virus. People with chronic liver disease, including those with hepatitis C, should also be vaccinated, particularly if they have not been exposed to hepatitis A, since the infection can cause liver failure in these patients.

The hepatitis A vaccine can be given along with immune globulin and other vaccines. Individuals should also receive immune globulin if they are exposed within 4 weeks of the vaccination. A combined vaccine against both hepatitis A and B is now available as well, for those at high risk for both these infections. People should get 3 doses of this vaccine, and the last dose should be given 6 months after the first dose. New 2010 immunization guidelines recommend that unvaccinated persons who anticipate contact with an overseas adoptee consider vaccination.

Side Effects. The vaccine is very safe and effective, although allergies can occur. The most common side effects reported are soreness at the injection site, headache, and general malaise.

Hepatitis B

About 2 billion people have been infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) worldwide, and each year 1 million people die, mostly due to cirrhosis and liver cancers that develop in the chronic form of this disease. In the U.S., about 1.25 million people have chronic hepatitis B.

Pregnant women with hepatitis B can transmit the virus to their babies. Even if they are not infected at birth, unvaccinated children of infected mothers run a 60% risk of developing hepatitis B before age 5. Although hepatitis B infections have dropped 95% since routine immunization began in the early 1990s, there are still children who aren't immunized, and the disease persists. Universal vaccination against this disease during childhood is very important.

Vaccine for Hepatitis B

Several inactivated virus vaccines, including Recombivax HB, GenHevac B, Hepagene, and Engerix-B, can prevent hepatitis B. Twinrix is a vaccine against both hepatitis A and B. These vaccines are safe, even for infants and children. Vaccination programs are proving to reduce the risk for liver cancer.

Hepatitis B Vaccine for Early Childhood. Experts now recommend that all infants and children not previously vaccinated be immunized by the time they reach seventh grade. Typical schedules for hepatitis B vaccinations in childhood are as follows:

- All infants should receive the hepatitis B vaccine soon after birth and before hospital discharge. (The first dose may be delayed if the mother has no evidence of infection, but only with the doctor's permission.) The second dose should be given at 1 - 2 months; and the third between 6 and 18 months (at least 16 weeks after first dose and 8 weeks after second dose). (A fourth dose may also be given if any of the previous doses was a combination vaccine.) This is a safe vaccine, even in newborns, and parents should be sure their infants are immunized.

- Infants of mothers infected with hepatitis B should be treated with immune globulin plus the hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth. The second dose should be given at 1 - 2 months and the third at 6 months. Infants born to infected mothers should be tested for antibody status at 9 - 18 months to see if they are chronic virus carriers or need to be revaccinated. Immunization rates are still too low in this group.

- When it is not known if a mother is infected, the infant should receive the vaccine within 12 hours of birth. The mother's blood should then be tested right away. If she is infected, the infant should receive immune globulins within 1 week of birth.

- Children who are 11 - 12 and who have not been immunized should receive 2 or 3 doses of the vaccine (depending on the brand) given over a few months.

Hepatitis B vaccine protection may wane over time. Declining immunity has been shown in adolescents vaccinated when they were newborns. As of now, routine booster shots are not recommended because more research is needed on the subject. Booster shots may be recommended for those at risk, such as from sexual exposure.

Hepatitis B Vaccine for Adults. The following adults are at high risk and should be vaccinated:

- Health care and public safety workers who may be exposed to blood products. Such individuals have a risk for hepatitis B that ranges from 15 - 30%.

- People in the same household as hepatitis B-infected individuals. (Unvaccinated people who have had intimate exposure to people with hepatitis B may be protected with immune globulin, which is sometimes administered with the vaccine.)

- Travelers to countries with a high incidence of hepatitis B infection.

- Patients who require transfusions and have not been infected with hepatitis B. (Those with blood clotting disorders should have the vaccination administered under the skin, not injected in the muscle.)

- Sexually active individuals with multiple partners.

- People with any sexually transmitted diseases.

- Patients with diabetes under 60 years of age, or older diabetic patients who use glucose monitoring devices or have other risk factors.

Other people at risk who would benefit from vaccinations include:

- Patients and workers in mental institutions

- Morticians

- Patients undergoing hemodialysis (these people may need larger doses or boosters; they also may need to be revaccinated if blood tests indicate they are losing immunity)

- People who use injected drugs

- Pregnant women at risk for the virus (there is no evidence that the vaccine is dangerous to the fetus)

- People receiving treatments or who have conditions that suppress the immune system may need the vaccination, although its benefits for this group are unclear except for those at high risk, such as people with HIV or spleen abnormalities.

The regimen in adults is typically 3 doses given over 6 months. People who abuse alcohol may need additional doses.

A small percentage of people do not develop immunity, even after a vaccine has been given repeatedly. A more potent vaccine is proving to be effective for these people; it loses its effect after 5 years in about one-third of those who receive it.

Side Effects of Hepatitis B Vaccine

Soreness. Soreness at the injection site is the most common side effect.

Nerve Inflammation. There have been reports of nerve inflammation after vaccinations for hepatitis B, and some questions about multiple sclerosis. However, studies and reviews have found no real evidence linking the vaccine to a number of disorders.

Due to even the small theoretical risk of nerve damage in infants, some groups oppose the vaccination in children who are not in high-risk groups. However, this risk must be balanced against the significant reduction in chronic hepatitis and liver cancer cases due to this vaccine, especially around the world. [For more information see In-Depth Report #59: Hepatitis.]

Pneumococcal Pneumonia

The pneumococcal bacterium (also called Streptococcus pneumoniae or S. pneumoniae) is responsible for many respiratory infections in the upper and lower airways. This bacterium is dangerous for people with serious underlying chronic medical conditions and illnesses, and is the leading cause of ear infections and sinusitis in children. The most common type of severe S. pneumoniae infection is pneumonia.

Vaccine Description

The pneumococcal vaccine protects against some strains of S. pneumoniae bacteria, the most common cause of respiratory infections. There are 2 effective vaccines available:

- The 13-valent (strain) pneumococcal conjugate vaccine Prevnar (PCV13) for all infants and children below five years of age.

- The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax, Pnu-Immune) or PPSV23 for some adults and older children.

Candidates for the Pneumococcal Vaccine

The new 13-valent conjugate vaccine Prevnar (PCV13) replaces its previous version, PCV7, and is very effective in children. The vaccine has reduced hospital admissions for pneumonia in children under age 2 by up to 40 %. The vaccine has even lowered hospital admissions among adults aged 18 - 39, likely because they are parents of young children who might otherwise have been exposed to the disease. Recurrent ear infections in children have fallen by 28% since the introduction of the vaccine.

The recommended schedule of immunization for Prevnar (PCV13) is 4 doses, given at 2, 4, 6, and 12 - 15 months of age. Infants starting immunization between 7 and 11 months should have 3 doses. Children starting their vaccinations between 12 and 23 months only need 2 doses. Those who are over 2 years old need only 1 dose.

A PCV13 vaccine for adults is being studied but has not yet been approved.

The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine or PPSV is recommended for the following older children and adults:

- Anyone older than two years of age with heart disease, lung disease (including asthma), kidney disease or on dialysis; alcoholics, people with diabetes, cirrhosis, or those with cochlear implants or leaks of cerebrospinal fluid.

- All people over 65 years old; some experts believe that all adults aged 50 - 64 should also be vaccinated. Adults over 65 who received a pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine before they were 65 should receive a second dose after they turn 65.

- Adults aged 19 - 64 who have asthma or smoke should receive a single dose of PPV.

- Those with sickle cell disease

- Those with a nonworking spleen and those who have had their spleen removed (should receive a second vaccine five years or more after the first dose)

- Persons with conditions that weaken the immune system, such as cancer, HIV infection, or organ transplantation

- Persons who receive chronic (long-term) immunosuppressive medications, including steroids

- Individuals with immune deficiencies or those undergoing treatments that suppress the immune system (should receive a second vaccine 5 years or more after the first dose)

- Patients with autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, although protection may not be as strong for these patients.

- Older people who have had transplant operations or those with kidney disease may require a revaccination after 6 years.

- People living in long-term care facilities.

- Alaska Natives or Native Americans over age 65 who live in areas with high rates of invasive pneumococcal disease. In certain communities, public health authorities may recommend vaccination for those 50 - 65 years of age, or younger.

The safety of the pneumococcal vaccine hasn't been proven during the first trimester of pregnancy; however, there have been no adverse effects reported. When the vaccine is administered to pregnant women, it may actually protect their infants against certain respiratory infections.

Protection lasts for more than 6 years in most people, although the protective value may be lost at a faster rate in elderly people than in younger adults. Anyone at risk for serious pneumonia should be revaccinated 6 years after the first dose, including those who were vaccinated before age 65. Subsequent booster doses, however, are not recommended.

Quitting smoking significantly reduces a person's risk of contracting pneumococcal disease.

Side Effects of the Pneumococcal Pneumonia Vaccine

Side effects include pain and redness at the injection site, fever, and joint aches. Children are more likely to have fever within 48 hours if they receive other vaccines at the same time, and also after the second dose. Fortunately, severe reactions are very rare, even if a person is mistakenly revaccinated before the effects of the first vaccination have worn off. Allergic reactions are also very rare.

Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, more commonly known as polio, is a disorder caused by a virus and marked by potentially paralyzing nerve-related damage, which can be fatal. Fifty years ago it was a major killer of children, and it remains a threat in parts of Asia and Africa today. Vaccination programs eliminated the disease in the Americas in 1994, with the last case of wild poliovirus in the U.S. reported in 1979. As of 2004, polio has been eradicated in the Americas, the Western Pacific, and Europe.

Vaccines for Poliovirus

Two poliovirus vaccines have been available in the U.S.: oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), a live-virus vaccine, and inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), a killed vaccine that is administered by an injection. Both produce immunity in more than 95% of people. The live-virus used in the vaccine, however, has in some cases, reverted to a form that can cause polio in unvaccinated people. This is a particular danger in developing countries where vaccination rates are low. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends only the inactivated IPV vaccine for children. The schedule is 4 doses of IPV at ages 2 months, 4 months, 6 - 18 months, and 4 - 6 years.

Poliovirus Vaccine in Older Children and Adults. The poliovirus vaccine is not usually recommended for people over 18. Exceptions are unvaccinated health care workers, laboratory technicians, or others exposed to polioviruses. Travelers to developing countries where outbreaks of poliovirus have been reported should be vaccinated. Adults who need protection should also be given the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV).

Side Effects of the Poliomyelitis Vaccines

Allergic Reactions. The inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) contains small amounts of streptomycin and neomycin, so people allergic to these antibiotics can also have an allergic response to this vaccine. Patients should report any allergies to their physician.

Paralysis. Rare cases of paralysis have occurred in people taking the oral live poliovirus vaccine or in those exposed to recipients of this vaccine. It should be stressed the risk is very small, with only 1 case occurring out of 2.4 million doses. Since the introduction of the current recommended series that uses only IPV, no cases have been reported. Polio, once a major killer of children, has nearly been wiped out worldwide.

Viral Influenza

Influenza, commonly called the flu, is always caused by a virus.

There are different strains of influenza:

- Influenza A is the most widespread and most severe strain. It can affect both animals and humans. Influenza A is the cause of all the worldwide epidemics (pandemics) of the flu that have occurred. Influenza is responsible for over 200,000 hospitalizations a year in the U.S.

- Influenza B infects only humans. It is less common than type A, but is often associated with specific outbreaks, such as in nursing homes. Flu caused by this strain tends to be milder than that caused by Influenza A.

The 2009 H1N1 "Swine flu" pandemic was a new strain of influenza A.

Complications of the Flu. Pneumonia is the major serious complication of the flu and can be very serious. It can develop about 5 days after viral influenza. It is an uncommon event, however. It nearly always occurs in high-risk individuals, such as the very young or very old, pregnant women, and hospitalized or immunocompromised patients.

The largest number of H1N1 flu cases occurred in people ages 5 - 24. Fewer cases and deaths have been reported in people older than age 64. This is a different pattern than that seen with the seasonal or regular flu outbreaks.

[For more information, see In-Depth Report #94: Colds and the flu.]

Flu Vaccines

Description of Vaccines. The influenza vaccine is designed to provoke the immune system to attack antigens on the surface of the virus. (Antigens are molecules that the immune system recognizes as alien and targets for attack.)

Unfortunately, the antigens in influenza viruses undergo genetic alterations (called antigenic drift) over time, so they are likely to become resistant to a vaccine that worked in the previous year. Vaccines are redesigned annually to match the current strain.

A vaccine for the H1N1 (swine flu) strain was released in the fall of 2009. This vaccine did not take the place of the seasonal flu vaccine, but was an additional vaccine available to those in high risk groups. A similar strain has now been included in the seasonal flu vaccine.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is recommending the following three viruses in the 2012 - 13 seasonal flu vaccine:

- an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- an A/Victoria/361/2011 (H3N2)-like virus

- a B/Wisconsin/1/2010-like virus (from the B/Yamagata lineage of

viruses)

There are several types flu vaccines/delivery systems. The flu vaccine can be injected into the skin (intradermal), into the muscle (intramuscular), or inhaled as a nasal spray.

The flu injection contains killed (inactive) viruses. It is not possible to get the flu from this type of vaccine. The flu injection is approved for people age 6 months and older. Various formulations are available. A preservative-free vaccine (Fluzone) is also available.

Most adults have received the intramuscular vaccine in the upper arm. Babies and young children are commonly vaccinated in the upper thigh.

Two new vaccines were released in the spring of 2011, Fluzone Intradermal and Fluzone High Dose.

Fluzone Intradermal

Fluzone Intradermal is a single shot on the skin for adults aged 18 to 64 years old. It contains less of the inactivated virus than the intramuscular preparations and delivers the injection with a smaller needle. Temporary adverse reactions may include pain, itching, swelling and redness of the skin at the injection site.

Fluzone High Dose

Fluzone High Dose is available for persons age 65 and older. It contains four times the amount of inactivated vaccine compared to a regular flu shot. A greater immune response has been seen in older adults who receive the high dose vaccine, but whether or not it offers greater protection from the flu will become more clear when ongoing studies are completed in 2014 - 2015.

The Nasal spray flu vaccines use a live, weakened virus instead of a dead one.

- It is engineered to multiply in the cool temperatures of the nasal passages, but not in the warmer lungs and lower airways. Its presence in the nasal passages boosts the specific immune factors in the mucous membranes that fight off the epidemic flu viruses.

- It is approved for healthy people ages 2 - 49, who are not pregnant. It should NOT be used in those who have asthma or in children under age 5 who have repeated wheezing episodes.

The avian flu vaccine is designed for people aged 18 - 64 who are at risk for exposure to the avian H5N1 virus. The vaccine is given as 2 doses, spaced about 1 month apart. In studies, the vaccine appeared to be effective and well tolerated. Currently, the government is stockpiling the vaccination in case of an avian influenza outbreak. The vaccine is not available to the general public.

Timing and Effectiveness of the Vaccine

Ideally, appropriate candidates should be vaccinated every October or November. However, it may take longer for a full supply of the vaccine to reach certain locations. In such cases, the high-risk groups should be served first.

Antibodies to the flu virus usually develop within 2 weeks of vaccination, and immunity peaks within 4 - 6 weeks, then gradually wanes.

- Children 6 months to 8 years of age, require either 1 single or 2 vaccine doses, spaced 4 weeks apart, depending on the previous year's vaccination.

- It should be noted that if an individual develops flu symptoms and is accurately diagnosed in time, vaccination of the other members of the household within 36 - 48 hours affords effective protection to those individuals.

In healthy adults, immunization typically reduces the chance of getting the seasonal flu by about 70 - 90%. The current flu vaccines may be slightly less effective in certain patients, such as the elderly and those with certain chronic diseases. Some evidence suggests, however, that even in people with a weaker response, the vaccine is usually protective against serious flu complications, particularly pneumonia. Some evidence suggests that among the elderly, a flu shot may help protect against stroke, adverse heart events, and death from all causes.

Because the H1N1 (swine) flu vaccine is so new, there is not a lot of data about its effectiveness to prevent this strain of the flu. However, studies of the vaccine before it was released showed that people formed antibodies to the H1N1 flu in a similar manner to the regular or seasonal flu.

Candidates for the Flu Vaccine

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the CDC recommend regular or seasonal flu vaccinations for all healthy children ages 6 months to 18 years (inclusive).

The CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice (ACIP) recommends that all persons (healthy as well as higher risk) 6 months of age or older receive annual flu vaccination unless otherwise contraindicated. This recommendation replaces previous guidelines focused on high-risk individuals.

Side Effects

Possible side effects of the flu vaccine include:

- Allergic Reaction. Newer vaccines contain very little egg protein, but an allergic reaction still may occur in people with strong allergies to eggs.

- Soreness at the Injection Site. Up to two-thirds of people who receive the influenza vaccine develop redness or soreness at the injection site for 1 or 2 days afterward.

- Flu-like Symptoms. Some people actually experience flu-like symptoms, called oculorespiratory syndrome, which include conjunctivitis, cough, wheeze, tightness in the chest, sore throat, or a combination. Such symptoms tend to occur 2 - 24 hours after the vaccination and generally last for up to 2 days. It should be noted that these symptoms are not the flu itself but an immune response to the virus proteins in the vaccine. (Anyone with a fever at the time the vaccination is scheduled, however, should wait to be immunized until the ailment has subsided.)

- Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Isolated cases of a paralytic illness known as Guillain-Barre syndrome have occurred, but if there is any higher risk following the flu vaccine at all, it is extremely small (one additional case per 1 million people), and does not outweigh the benefits of the vaccine.

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B

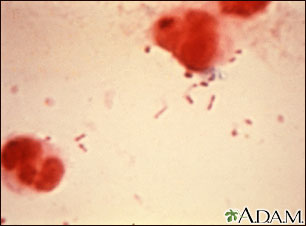

Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) type b is a bacterium, which, despite its name, is entirely different from the viruses that cause influenza (the flu). Before vaccination, H. influenzae type b (Hib) was the most common cause of childhood bacterial meningitis, killing 600 American children every year and leaving others deaf, mentally retarded, or epileptic. It is rarely troublesome for adults, although it can be dangerous for anyone with chronic lung disease and those susceptible to infections.

Meningitis Vaccine

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice (ACIP) now recommends booster vaccinations of the MCV4 meningitis vaccine for people who are at increased risk for the disease. These include people who do not have a normal spleen and those with certain immune problems.

Vaccine for Haemophilus Influenzae Type B

Two equally effective inactivated bacterial vaccines (commonly called Hib vaccines) are available for H. influenzae type b. All children under 5 should be vaccinated against this bacterium. The vaccine is administered as an injection at 2 and 4 months. Depending on the vaccination preparation, a third shot in the series is administered at 6 months. A booster is required at some time between 12 and 15 months of age.

The Hib vaccine may benefit older people who have had their spleen removed or have illnesses that put them at risk for pneumonia, including sickle cell disease, leukemia, and HIV infection.

Side Effects of Haemophilus Influenzae Type B Vaccine

Side effects of the Hib vaccine include redness and pain at the injection site, moderate fever, and, in rare cases, weakness, nausea, and dizziness.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV is actually a group of 100 viruses, about 40 of which are sexually transmitted. Some HPV viruses can significantly increase the risks of cervical cancer, as well as cancers of the vulva, vagina, anus, and penis. HPV is very common; an estimated 20 million people in the U.S. have it. At least half of all sexually active men and women will eventually be exposed the virus.

Two vaccines have been approved and are now recommended for the prevention of some types of HPV. Both vaccines protect against HPV strains 16 and 18, which account for 70% of cervical cancer cases in the United States.

- The Gardasil vaccine is nearly 100% effective against cervical, vaginal, and vulvar diseases caused by 4 types of HPV (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18). It is not effective in women who were exposed to these strains before vaccinated. The vaccine has been shown to be effective for at least 5 years after women receive the initial dose. In September 2008, the FDA also approved Gardasil for the prevention of vaginal and valvular cancers caused by HPV 16 and 18.

- A new vaccine, Cervarix, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in October 2009. This vaccine protects against HPV strains 16 and 18 only. As such, it will not prevent genital warts but would still protect against the strains that cause the majority of cervical cancers.

Who Should be Vaccinated for HPV?

Currently, two vaccines are approved by the FDA to prevent either human papillomavirus (HPV) or cervical cancer: Gardasil and Cervarix.

Gardasil is approved for:

- Girls and women ages 9 - 26, for the protection against HPV-16 and HPV-18, the HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer, and against HPV-6 and HPV-11, which cause 90% of cases of genital warts.

- Boys and young men ages 9 - 26 years to prevent genital warts

Cervarix:

- Girls and women ages 10 - 26 for protection against HPV-16 and HPV-18, the HPV strains that cause most cases of cervical cancer.

- Cervarix does not protect against genital warts.

- Cervarix has not been approved for use in boys or men.

Current immunization guidelines recommend: